An exploration into Europe’s quest for green transition materials and the tensions arising from it.

Kiruna’s Environmental and Cultural Price

Kiruna, situated in northern Sweden, is under threat. With the excessive excavation activities for iron ore mining, the town’s stability is compromised. Officials are now forced into relocating the entire city center, financed by state-owned mining firm LKAB.

This move isn’t without controversy, as Karin Kvarfordt Niia, a representative of the indigenous Sámi community, laments:

“This has been 130 years of encroachment on our nature and abuse of us Sámi in this area.”

Further plans by the mining company and the Swedish government to tap into new rare earth elements intensify the conflict, offering a stark contrast between envisioned economic prosperity and the gradual erosion of the Sámi way of life.

Niia continues:

“They have dried up lakes where we used to fish. They have taken away from us areas where our reindeer have grazed forever. We have had to move from our villages.”

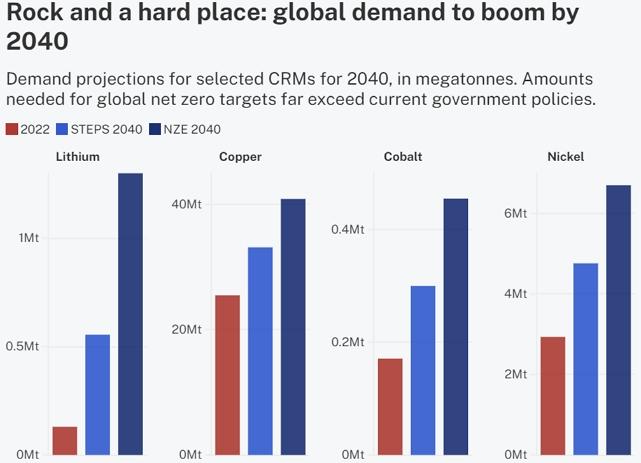

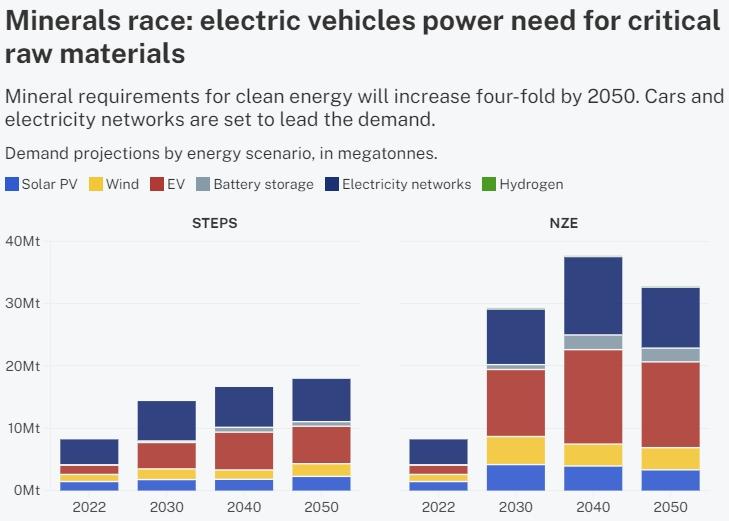

The Rising Importance of Rare Minerals in a Green Age

As coal fueled the 19th century and oil the 20th, the 21st century pivots on rare earth elements. These metals, including lithium, cobalt, and nickel, are fundamental for:

- Green energy transition;

- Defense and space industries;

- Consumer electronics like smartphones and laptops.

However, the challenge lies in sourcing them. Europe’s dependency on imports, especially from countries like China, poses a significant risk.

Thierry Breton, EU Commissioner for the internal market, emphasizes this concern:

“Our main concern is excessive dependencies, meaning dependency on a single source of supply. When we have such dependencies and Ukraina is at war, or China bans exports, or there is an earthquake in Chile, we can have a problem.”

Europe’s Push for Independence

To counteract this over-reliance, Europe is looking inward. New mining projects are emerging, with discussions on ‘green mining’ becoming more frequent in Brussels.

One such instance is LKAB’s recent discovery of a massive deposit of rare earth minerals in Kiruna.

During a related event, energy minister Ebba Busch stated:

“This discovery is a key to the green transition, not just for Sweden but for Europe.”

Yet, challenges persist. Even if Europe manages to mine these minerals, the processing infrastructure is largely absent.

Stephane Bourg of the French Geological Survey mentions:

“At this very moment, if we would produce rare earths in the EU, they would have to go through China (or at least Asia) for some transformation steps into a magnet.”

Mining’s Political Landscape and Controversies

The European Commission’s efforts to reverse dependency include the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA). The proposal emphasizes:

- At least 10% of the EU’s annual consumption for extraction.

- A maximum of 65% of the EU’s annual consumption from a single external country.

However, these endeavors aren’t without detractors. Friends of the Earth criticizes:

“CRMA in its current form is a clear example of corporate capture.”

Across Europe, the struggle to find a balance between economic growth and environmental conservation is evident. Protests and debates surround mining projects, especially in ecologically sensitive regions.

Carla Gomes, an activist from Portugal, poignantly says:

“Some things are priceless. Once those mountains are turned into mines, they will never be mountains again and nothing will ever be the same again.”

Yet, the demand for these materials remains, leading some to frustration.

Peter Tzeferis, a senior mining official in Greece, exclaims:

“They want a phone – and a cheap one at that! – but refuse to consider what minerals are needed and where they come from.”

With such polarized views, the pathway to a green transition in Europe remains challenging and multifaceted.

Unearthing Europe’s Dormant Mining Potential

The true scale of Europe’s mineral resources is largely undiscovered, as significant geological surveys haven’t been conducted in nearly half a century. Europe’s shift away from its extractive sectors is one of the main reasons for this neglect.

Alecos Demetriades, a retired mining and exploration geologist at the Hellenic Geological Survey in Athens, says:

“China is constantly exploring for new deposits, unlike us in Europe that have stopped systematic mineral exploration.”

The Struggle of Approvals and Funding

While exploration is paramount, moving from exploration to mining is no easy feat. Approval processes are extensive, with permits taking years to acquire. This bureaucratic delay has driven a push for the CRMA to streamline the process.

Margrethe Vestager, the EU Commissioner in charge of competition, commented:

“No strategy will come to life without investments. The money should not come through the Commission, which is a huge bureaucracy, not a bank.”

However, despite these calls for action, the Commission hasn’t designated a unique fund for the CRMA. While the U.S. has allocated substantial resources for their green transition, Europe seems to lag. Instead, the Commission has suggested that member nations utilize their budgets for mining initiatives.

European Mining: The Current Landscape

The European landscape for mining is thin. Only a small percentage of the world’s largest mining companies hail from Europe. With the immediate need for raw materials for green transitions, the challenges for the EU are immense.

However, while Europe grapples with these challenges, China’s strategic long-term thinking has positioned it as a dominant force in the industry.

“The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths,” said Deng Xiaoping in 1987.

Furthermore, China’s dominance isn’t just in mining, but also in refining.

James Kennedy, an American mine owner consulting the US government on rare earths, explains:

“China controls the materials in the refining and metallic level. They don’t care who mines the stuff.”

The Environmental Cost of Rare Earth Metals

Despite their name, rare earth metals are abundant. However, extracting them requires moving vast quantities of rock, often resulting in environmental concerns.

This process, along with the associated environmental ramifications, has driven many Western companies to outsource their mining and refining to China, a decision with far-reaching implications.

EU’s Outreach Beyond Its Borders

With the unlikelihood of a sudden surge in European mining, the EU has shifted its focus globally. EU Commission president Ursula von der Leyen’s recent visits to Latin American countries and various partnership signings highlight this strategic pivot.

An EU diplomat indicated that while these partnerships are a temporary solution, the EU expects the same standards as practiced within Europe.

The Paradox of the Green Transition

Some regions in Europe, like Kiruna, are experiencing firsthand the implications of Europe’s new ambitions. Despite the promises of a green transition, the environmental and societal impacts are evident.

Håkan Jonsson, president of the Swedish Sámi Parliament, remarks:

“For us, the green transition becomes a black transition.”